The internment of all individuals of Japanese descent during WWII, including those born in Canada, is yet another dark period in Canadian history.

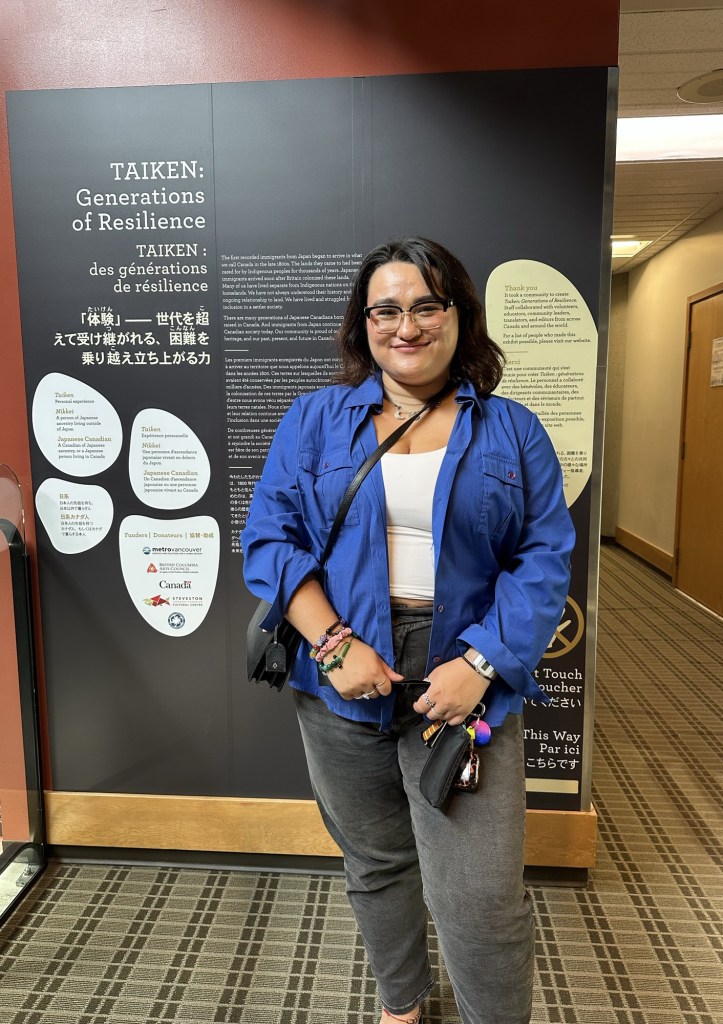

Last month, my family was able to take a trip to BC to visit the Nikkei National Museum and Cultural Centre and various internment camp sites, including where our grandmother spent part of her childhood.

In 1942, our great-grandfather was arrested in Vancouver by the RCMP and declared a POW for protesting the impending separation from his family. When he was arrested, he begged to call his family to let them know what happened and was granted permission on the condition that he did not speak in Japanese. When my great-grandmother handed the phone to my 5 year old grandmother, she spoke to him in Japanese, asking what happened. The RCMP officer ended the call immediately.

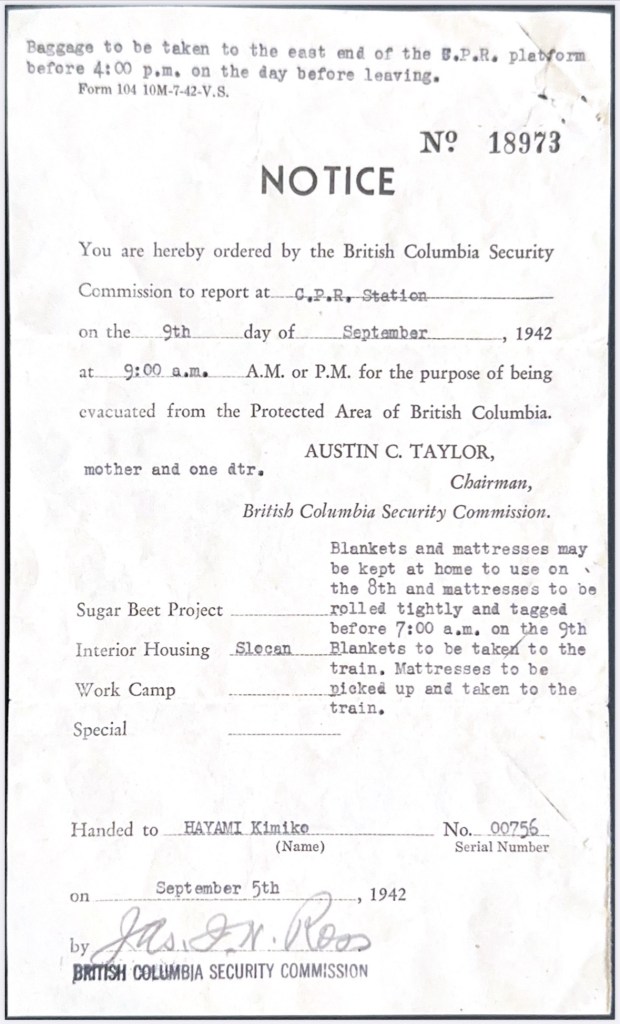

Later that year, our great-grandmother received a notice that she and our grandmother had to leave the area immediately.

All physically fit males over 18 were separated from their families and evacuated from Vancouver. Women and children, along with the elderly and disabled, were to be relocated separately.

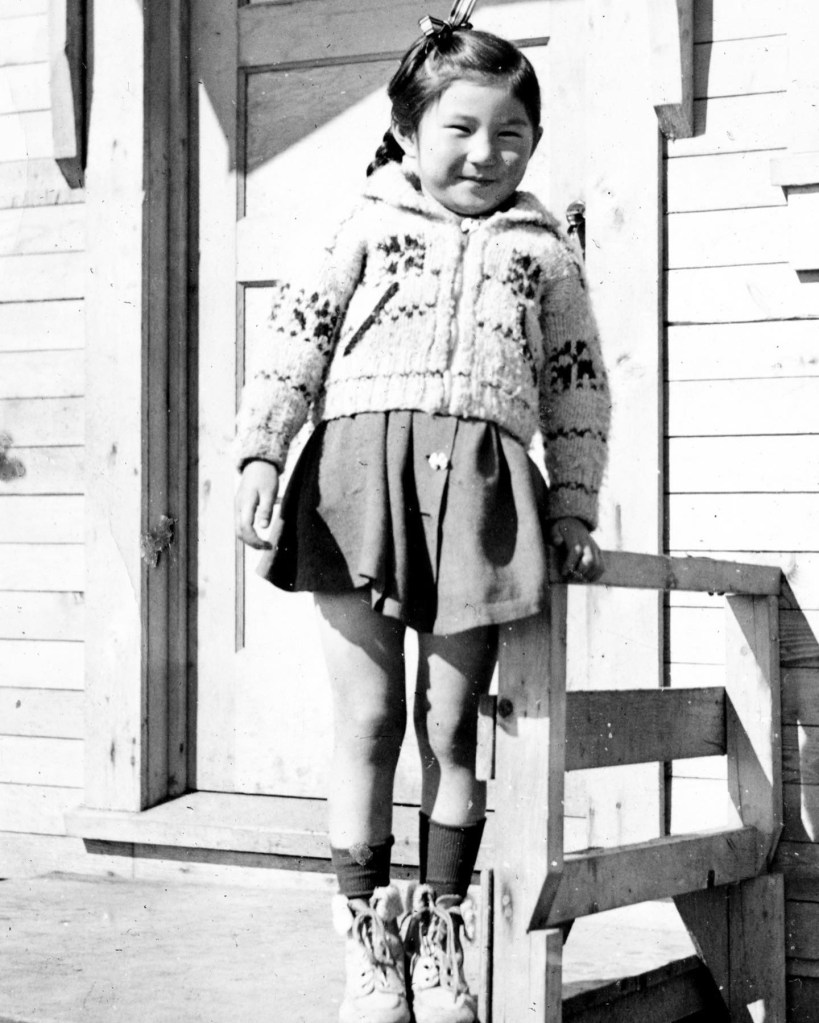

Grandma and her mother occupied cattle stalls at Hastings Park while waiting to be shipped off to interior BC. They hung blankets at the entrance to try to create a sense of privacy.

That winter was one of the coldest on record, and most families were forced to live in tents, or, if you were lucky, a shack without window panes or anything to keep the cold out. My grandmother recalled her mother trying to use newspapers to cover the windows and keep the cold out.

At the POW camp where my great-grandfather was sent, the men earned 25 cents an hour working at road camps, but were charged $20 for their boarding and each of their dependents. They wore jackets with a large circle on their back, initially believing it was a symbol representing their ancestry due to its similarity to the Japanese flag — but the circle was actually a target to make it easier for the guards to shoot their prisoners should they try to escape.

My great-grandfather remained a POW and was eventually sent to be a groundskeeper at an internment camp for German and Italian POWs in northern Ontario. While he was finally able to reunite with his family once my grandmother and her mother were permitted to join him there, they were displaced yet again.

After the war, the family tried to move to Toronto, but were told they were not allowed to due to the number of Japanese Canadians that had already relocated there, and that they needed to go elsewhere. That is when they ended up settling in Montréal, where, years later, my grandmother met my grandfather.

Like with every Japanese Canadian interned during that period, our family’s property was confiscated by the government and auctioned off for a fraction of their value. Heirlooms, our great-grandfather’s boat, their property, gone — just like that. Of the 22,000 dispossessed, only one man, a Japanese Canadian WWI veteran, was able to retrieve his property after the war ended; only with the assistance of his former commanding officer.

Grandma and her parents were actively involved in the 1988 Redress where the community sought to receive a formal apology from the Canadian government. They were successful, and an official apology from PM Brian Mulroney and financial reparations were received. Each individual interned received $22,000, equivalent to approximately $60,000 today; however, that does not even begin to account for what was lost.

Intergenerational trauma is tricky — you often don’t know it even exists in your family, and sometimes you refuse to believe it does. We always knew about the internment, that Grandma spent her formative years in these camps. However, seeing it in person was life changing, it finally felt real. The subjection to harsh weather, the inhumane conditions, everything we never learned in school. The camps were built on Indigenous lands. Dispossession on dispossession.

Throughout the trip, we asked ourselves: “Is this heritage something I want to keep carrying, or do I want to let go?” But I can’t let go, not yet. Not when this story is virtually unknown to the majority of Canadians.

Seeing everything in person, having everything suddenly feel real, was undeniably difficult, but seeing the way the community flourished after the war, all the individual and group achievements, the way everyone came together for the Redress, that brought us hope. That brought us healing.

Sometimes you have to survive because that is the only option. That was their only option. Knowing Grandma built the life she did, with a happy marriage, three daughters, and a successful career as an educator, is one of many examples of strength and resilience within the Japanese Canadian community post-internment.

The moments of tremendous courage and resilience displayed by Japanese Canadians throughout the war brings us a sense of healing, like my great-grandfather being taken into custody standing up to the authorities to try and stay with his family, to keep other families intact.

Despite it all, we are still here, proud of our heritage, and nobody can take that away from us.

Leave a comment